Salt Lake City-based Sweet Candy Company is a 100-year-plus-old confectioner that’s on its fourth generation of family ownership and leadership, with the fifth generation already coming up in the business. Founded by the Sweet family, the company distributes more than 250 high-quality candy items nationally and internationally in bulk, in bags, and in cartons. But it’s perhaps best known for a signature, chocolate enrobed stick-shaped candy that’s sold exclusively in 10.5-oz cartons. A regional favorite since it first debuted in the 1940s, the indulgent chocolate and fruit-flavored pectin treat is sold year-round. But there also had been a seasonal element to sales patterns; as a popular stocking stuffer in the intermountain region, the chocolate sticks had locally become practically synonymous with the holidays.

But these chocolate sticks are no longer a regional secret having recently acquired more of a national following via specialty candy markets that sell them as giftable, sharable gourmet treats. Sweet’s chocolate sticks can now be found nationally at retailers like Cracker Barrell Old Country Stores, Ross stores, or other candy markets that specialize in unique products outside of traditional mass merchant or grocery formats. Since the chocolate sticks are unitized as 10.5-oz with 32 to 34 chocolate sticks per carton, the price per ounce is a leader in the real chocolate category. And for a store like Cracker Barrell, this drives full margin on the product. A modular design allows for many different functions within the system, including collating individual product from a loosely arranged infeed, whole-layer picking and placing into carton bottoms, wax paper application, and carton lidding.

A modular design allows for many different functions within the system, including collating individual product from a loosely arranged infeed, whole-layer picking and placing into carton bottoms, wax paper application, and carton lidding.

This recent entrance into national specialty candy markets precipitated a growth in demand over the entire year—not just during that seasonal holiday rush—forcing leadership to start thinking about making big moves in automation to keep up with increasing production demands. These moves weren’t strictly production- or throughput-based, either. Leadership intended on increasing a level of precision in weights, sizes, and counts that it couldn’t previously maintain with a more semi-automatic packaging line. But most urgently, it needed to improve packaging operations that have, especially for this product, lagged upstream candy-making capacity. So in October of 2022, just as the seasonal rush ramped up, the company made the move with a brand-new robotic primary packaging installation. And as is usually the case, downstream secondary and end-of-line packaging automation was upgraded to keep up in a cascade of new automation.

Never shy about visiting candy manufacturers, Packaging World recently took a visit to Sweet Candy’s immaculate 180,000-sq-ft production facility and distribution center to check out the new fully automated, one-carton-per-second boxed chocolate stick packaging line. It centers around a Schubert robotic primary carton-packing installation with advanced, space-saving counterflow technology. Here’s what we learned about the unique project.

Knowing when to take the plunge

When installed in 1999, the legacy equipment that the new system replaces had been state-of-the-art; it was an early example of pick-and-place technology that has since become ubiquitous in packaging of arranged candy multipacks. Second-generation owner Tony Sweet was perhaps ahead of his time when, after a global equipment search in the late 1990s, he sourced the equipment from Hannover, Germany’s Haytech GmbH & Co.KG. But according to Geoff Dziuda, current VP of operations at Sweet Candy Company, the pneumatic, single-head gantry pick-and-place equipment from a now-defunct German OEM was reaching the end of its useful life 20 years later.

“The prior equipment had done a great job of getting us from the time that the Sweet family decided to move into this building, up until the present day,” he says. “But we wanted to be able to add capacity to keep up with the [chocolate stick] demand that we were seeing, and we wanted to be able to add another shift. We could see the existing equipment just wasn’t the right machine for the future growth that we were looking at.”

In part, that’s because the case packing equipment had never been designed to pair one-to-one with the upstream processing equipment. Intentionally, right out of the gate, it was a step slow, as it had been specified to handle 80 to 85%, at best, of the upstream product flow. Manual picking had augmented the machine from day one, and some small percentage of rejects would simply fall off the end of the infeed belt. But in recent years, that 80 to 85% number had dwindled to 50 to 60%. That meant that until recently, nearly half of product handling and cartoning operations had been manual, done by operators working alongside the declining equipment. Since Haytech had gone out of business, replacement parts were hard to come by, and the mechanics that had been trained on the equipment in 1999 had long since retired or moved on, the situation had become untenable.

“Especially in the current labor climate, we were faced with this issue of ‘how do we increase our throughput on this line?’” Dziuda says. “Because we had this old piece of equipment that could manage about 50% of our capacity, with the support of six operators to help it along. It had a lot of defects and neither its accuracy nor efficiency were up to modern standards.”

Exacerbating the issue, downstream case packing and palletizing operations had always been completely manual. So to get more capacity and throughput out of the line, absent new equipment, it would be a function of adding as much of the already scarce labor as Sweet Candy could find in smaller market Salt Lake City. That could be as many as 15 to 20 more people, and when considering “the variability that comes with manual labor, and their inefficiency, and just the added management for that amount of labor,” Dziuda says that automation was the obvious choice. So, he and Sweet’s fourth-generation president and CEO Rick Kay undertook yet another global search that this time landed them on Schubert robotic packaging equipment, with speed and accuracy that would precipitate a fully automated line downstream, right on down to palletizing.

Vendor selection factors

While much of the equipment on the chocolate sticks packaging line is new, the primary packaging piece—placing two of layers chocolate sticks into flat paperboard cartons—would set the tone for everything downstream. Delta-style robots for picking and placing were the preferred technology among the finalist vendors seeking to supply Sweet’s with this equipment. But Dziuda had been acquainted with Schubert equipment from a previous role, so he added the company to the short list. Though it offers delta-style options as well, Schubert suggested its SCARA-style F4 mulit-axis pick-and-place robots as a better fit for the project. The German OEM with U.S. headquarters in Charlotte, N.C., ultimately won the contract for a host of reasons.

One primary consideration was a comparatively small footprint, “because we’re landlocked,” says Kay. “It’s a plenty big machine, but it fits.”

The machine’s footprint is able to be constrained because Schubert’s counterflow technology (patent recently expired) allows more operations to happen within a smaller space compared to a standard, mono-directional downstream belt. Using the counterflow concept, individual products run past one another, in parallel but in opposite directions, akin to several multi-lane highways within a single cell composed of as many individual modules as are needed to get the job done. The F4 robots pick and place the product between five parallel, but contra-directional belts, so neither the product nor the belts need to turn 180 deg on their own in order to continue downstream. Conceptually speaking, with counterflow, downstream doesn’t mean mono-directionally downstream. Instead, downstream product travels against the current of upstream operations, but still travels downstream. Gentle handling was another consideration, as the enrobed chocolate product is fragile and can’t withstand too much jostling. The infeed belt (A) carries product arranged in a 34- x 4-ct pattern. Parallel but contra-directional to the infeed are belts of product layers of 16 or 17 sticks (B) that have been picked and collated by SCARA robots further downstream. Parallel but contra-directional to the layer belts are carton lid and bottom infeed belts (C). The two SCARA robots in this image (D) are picking and placing whole layers of product into carton bottoms, after which wax paper will be applied and a second layer of product added for a finished 32- or 34-ct carton.

The infeed belt (A) carries product arranged in a 34- x 4-ct pattern. Parallel but contra-directional to the infeed are belts of product layers of 16 or 17 sticks (B) that have been picked and collated by SCARA robots further downstream. Parallel but contra-directional to the layer belts are carton lid and bottom infeed belts (C). The two SCARA robots in this image (D) are picking and placing whole layers of product into carton bottoms, after which wax paper will be applied and a second layer of product added for a finished 32- or 34-ct carton.

“That was a big topic of conversation for us,” Dziuda says. “We didn’t know how the sticks were going look after being handled by a robot at these volumes and speeds. We didn’t know what they were going to look like in the carton. Would the sticks be turned or were they going to be straight? Or could they be scuffed from a vacuum cup?”

As it turns out, all direct product handling was able to be accomplished by a custom-designed, 3D-printed vacuum end effector; no mechanical grippers are needed to handle the enrobed chocolate sticks. The result is gentle handling that’s indistinguishable from hand labor or the legacy equipment’s single pneumatic gripper.

“Maybe the most important to us was [Schubert’s] ability to meet the supply chain challenge. This was right around the middle to the tail end of the pandemic, and it was a time where we couldn’t get anything from anybody on time; everything was delayed,” Kay says.

A complicating factor was that the installation was targeted to occur in October of 2022, so just as the seasonal holiday rush began. The entire installation, from taking delivery to SAT to production, needed to happen fast.

“We had to get an army of people [to build up inventory ahead of the installation]. And it was painful,” Kay says, able to laugh about it now. “But it wasn’t like we were going to delay until January. So we prebuilt as much as we legitimately could, and we scrambled, and we worked. And we paid for airfreight to expedite the new equipment… we learned that from another project going on with a depositor; half of the stuff got stuck in the Panama Canal for months, and then the dock strikes slowed things down. What should have typically taken three weeks for shipping, pre-pandemic, took five months.”

This seasonal timing put the OEM under pressure to meet their deadline, and the customer-paid expense of airfreight hinged on the builder hitting the narrow time window. But Schubert builds a lot of its components—robots for instance—in-house. The company also sources many components from the region directly surrounding Schubert’s headquarters in Germany, shielding them from many more global supply chain issues.

“We pride ourselves on our manufacturing depth,” says Armin Klotz, sales account manager at Schubert North America. “Meaning 80% of what you see [in this installation] is built by Schubert. For instance, we built the vision system and the robots, and have been for 30 years. We never have had to delay a machine because we didn’t have a chip or a PLC.”

Adds Kay, “Schubert said it was going to be 38 weeks, and in exactly 38 weeks, the machines were delivered on time and installed ahead of schedule. They’re nimble; after all this is a product that they’ve never seen before. But since their machines are modular, with a certain range of robots able to do a certain range of tasks, they were quickly able to customize their more standard modules into running what we needed. It was so dialed in that we went from airfreight arriving to production in just two and a half weeks. That got our attention.”

“They have a menu of existing, modular options that you then customize,” adds Dziuda. “As we got into it, we had a few challenges. For instance, how were we going to add the wax paper in the middle of the two layers of chocolate sticks? Well, they just built a machine for that. Then the collation step [from loosely arranged product to layers based on weight, not count], that was something we had to develop with them. But their technologies and their experience aligned them well with this project for us, and that became evident to us early on. It was obvious that they had the capability, the acumen, and the experience to design something that would work for us.”

Upstream operations, and working with weights instead of counts

Individual batches of the pectin-centered chocolate sticks exhibit quite a bit of variability due to how they’re produced. That’s because they undergo a long, variable hardening and curing phase. This phase occurs between liquid pectin tray depositing into imprinted forming trays, and cured pectin product being removed from the trays to be conveyed toward chocolate enrobing. The fruit pectin-based candy centers start as a hot liquid candy slurry that is pumped via stainless pipes from kitchen kettles on an upper floor to be deposited into 34- x 4-ct forming trays. Once deposited, the trays of pectin centers run through an NID starch-depositing mogul candy line that cures the fillings in corn starch. These trays travel slowly through a series of connected tracks for a period of usually eight to 12 hours, firming up and cooling the hot liquid into a gummy-like candy consistency. After sufficient cooling in the mogul, and when the centers have reached the appropriate viscosity and consistency, the starch-packed centers are “bucked out” of their forming trays by inverting those trays over a belt, releasing the jelly centers to be conveyed downstream. The result is naked, loosely arranged product centers in repeated 34 x 4 rectangular configurations that are conveyed off the mogul line toward enrobing. In an added module, wax paper is cut from rollstock, and placed by SCARA robot with vacuum grippers between layers of product.

In an added module, wax paper is cut from rollstock, and placed by SCARA robot with vacuum grippers between layers of product.

“We love pectin, but if it’s in starch eight hours versus 14 hours, the moisture loss is going to change the density and the weight of the center. So, you have a variable there,” Kay says. “And then, that machine’s 25 years old, and starch-depositing moguls are finicky. And finally, there’s variability in the enrober which [at the time of PW’s visit was] on the verge of being replaced. Our chocolate coverage used to be a challenge, so that could lead to some variability.”

Ultimately, the finished stick weight could be all over the board. Yet Sweet’s was selling it by weight in 10.5 oz. cartons.

“So when we were hand packing, and we were just filling the carton, a 10.5-ounce box routinely had 13 ounces of candy—that’s a lot of giveaway,” Kay says.

With the new, flexible primary packaging line, operators simply weigh the first few cartons that come off the line. Depending on how close they are to the target mark of 10.5 oz without going under, they can simply toggle back and forth between 16- and 17-ct layers, or 32- or 34-stick cartons, to dial in the correct weight and count combination, with the least giveaway while still at or over 10.5 oz.

“If the checkweigher tells the operators that the cartons are too heavy, and they’re giving away too many products, then they can use the operator interface to punch a button, and remove a chocolate stick on the fly,” says Armin Klotz, Sales Account Manager at Schubert North America. “Usually you’d have to load a new program, but the software algorithm makes this possible on the fly, in real time, with just one button.”

Primary packaging

Enrobed chocolate sticks travel by belt for about 14 minutes through 180-ft of a 50°F cooling tunnel on their way to the Schubert system for primary packaging operations. At this point they’re loosely arranged in the aforementioned rectangular groupings of 34 x 4 sticks, with each grouping spaced a few inches apart. This single-belt configuration serves as the infeed, and while product isn’t randomly oriented, neither is it perfectly arranged. In an added module, wax paper is cut from rollstock, and placed by SCARA robot with vacuum grippers between layers of product.

In an added module, wax paper is cut from rollstock, and placed by SCARA robot with vacuum grippers between layers of product.

Product travels most of the way through the system, counterintuitively passing through and next to parallel downstream operations, before arriving in front of one of eight F4 high-speed, collating pick-and-place robots. These eight robots are arranged into two modules of four, with each module containing a 2x2 configuration of robots that pick product from the infeed belt. A vacuum-based end-of-arm tool on each robot picks three sticks at a time and orients them on one of two contra-directional collation belts that travel immediately to the right and left of the wide infeed belt. Pick-and-place pattern building, or collation of layers, continues by the eight robots until the desired 16- or 17-ct layers are achieved. The 2D and 3D vision systems are primarily looking for the position, orientation, and height of the sticks, to send to robots for accurate picking. But vision also looks for defects in color or out-of-spec stick dimensions. The system allows these rejected sticks to fall off the end of the belt as scrap when they’re identified.

The robots work from the outside in, with the first robots picking sticks on the edges of the infeed, and later robots working toward the remaining sticks in the middle. This action funnels the product into a “V” or triangle pattern of product as it travels downstream on the infeed toward the end of the belt. Near the base of the “V,” first sets of robots travel the fastest and complete the most movement, but also travel the shortest distance since they’re picking from the edges.

“This triangle or ‘V’ pattern means that when full 16- or 17-ct layers are close to being built—maybe there’s already 14 or 15 sticks in the layer and only one or two sticks are needed to complete it, there’s plenty of product available at the base of the triangle. The layers begin being built from the section of the infeed belt where product is most scarce and furthest downstream, at the peak of the triangle or ‘V,’” says Klotz. “The layer building and collation functions will never be starved for product, since the layers are closest to being completed exactly where the most product is available. Not only is there more product at the base of the triangle, that product is also nearer the edges. So product is closest to the waiting layers on the collation belt just when those layers most need a final stick or two to complete the layer, thus the robots have the shortest distance to travel to complete a layer.”

On the other side of the coin, the robots at the very end of the infeed are tasked with essentially cleaning up the remaining in-spec sticks from the very peak of the triangle, before they fall off and are hand-cartoned or worse, become scrap. At this point, the layers on the collation belt are the least full, so there are more available spaces to place them. If the layers were already full, robots may be forced to allow product to drop off since full layers mean there’s no spot to place the sticks. Whole layers of 16- or 17-ct product are cartoned by SCARA robots with vacuum grippers. The filled cartons are sold by weight, not count, and product weight can be variable by batch. So the system allows for on-the-fly changes from 16- to 17-ct to get a close as possible to the 10.5-oz target weight without going under, limiting giveaway of expensive chocolate.

Whole layers of 16- or 17-ct product are cartoned by SCARA robots with vacuum grippers. The filled cartons are sold by weight, not count, and product weight can be variable by batch. So the system allows for on-the-fly changes from 16- to 17-ct to get a close as possible to the 10.5-oz target weight without going under, limiting giveaway of expensive chocolate.

“Counterflow gives you a guarantee that you always have full, complete layers on the collation belt by the time they’re ready to be loaded into the carton,” Klotz says of this formerly proprietary system.

These layers of chocolate sticks are built on the collation belt as they travel in parallel to, but against the current of, the central product infeed belt. After the correct count is met, the entire layer is then picked up by one of four F4 layer-picking robots with larger, rectangular vacuum end-of-arm tools. The robots place each layer in an erected carton bottom that’s traveling on a cartoning belt. Once each layer is placed, it’s traveling in the same direction as the product infeed, against the current of the collation belt, and towards the end of the machine. With far more precision baked into the system than the mostly manual legacy operations, Sweet Candy is asking for more rigid lids from its paper carton converter to get the most efficiency out of its carton lidding operations.

With far more precision baked into the system than the mostly manual legacy operations, Sweet Candy is asking for more rigid lids from its paper carton converter to get the most efficiency out of its carton lidding operations.

Between each layer, yet another pair of robots, one on each side of the system, adds a sheet of wax paper—cut from rollstock on a specialized module—to the top of the first layer of chocolate sticks. After that, a second layer of chocolate sticks is added by another pair of robots with the same full-layer vacuum end effectors, finishing off the 32- to 34-count carton. Another pair of robots, one on each side, finally place the carton lid onto the caron base on the two-layer cartons, and they exit the Schubert system.

All told, this makes for seven parallel belts operating on Schubert’s counterflow principle within the system. In the center is one wide, central infeed belt. Directly to the right and left of the infeed are two product collation belts that travel back against the infeed flow to build layers of chocolate sticks. And finally, four carton infeed belts—two on each side, one for the bases, the other for the lids—enter the system parallel to the product infeed, outside of the collation belt. The carton lid infeed belt terminates as soon as lids are applied to the base. Outflow of the system occurs on three belts—some amount of rejects that were never picked exit for disposal at the terminus of the infeed belt, and the two carton belts on the right and left of the infeed travel downstream.

The system also houses a total of 16 Schubert F4 robots, grouped within modules to pick and collate product, pick layers of product and carton it, to add the wax paper, and to put the lids on the cartons.

Box shop and secondary packaging

Meanwhile, some sort of automation has to keep this intricate system fed with erected cartons. For box shop operations, Sweet’s uses two parallel pieces of legacy equipment from the original packaging line—mold plunge-style carton erectors by ADCO. One machine erects the carton bases, the other erects the carton tops. Operators load magazines of 2D cartons, printed by local supplier Utah Paper Box, for erecting to keep up with primary packaging operations. Cartons don’t require adhesive, and instead are held in shape by mechanical tabs. Lids and bases are laned into two, paired, lid and base conveyors, one pair for the right side of the system infeed, the other for the left. For the box shop, Sweet’s uses two parallel pieces of legacy equipment from the original packaging line—mold plunge-style carton erectors. One machine erects the carton bases, the other erects the carton tops.

For the box shop, Sweet’s uses two parallel pieces of legacy equipment from the original packaging line—mold plunge-style carton erectors. One machine erects the carton bases, the other erects the carton tops.

“The lid and base carton erectors are comparatively simple pieces of equipment, but we wanted to continue using those because of the familiarity we had with them, and they still work just fine. The speeds are sufficient to keep up, and our operators all know how to use them. Schubert was willing to work with us on integrating those older, but reliable pieces of equipment,” Dziuda says.

Leaving the primary packaging system are two lanes of finished cartons that make a 90-deg to the right, then may undergo some minor accumulation behind a turnstile gate that single-files the cartons on BW Integrated Systems conveyor equipment. The now-single lane of cartons again turns 90 deg to the right, then passes through a Sentinel checkweigher and metal detector by Thermo Scientific.

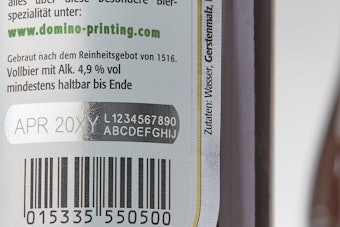

Laser coding is accomplished on a Markem Imaje C150, which Dziuda says provides neat, smudge-free date and batch codes without requiring the handling of any ink or input of other consumables. Checkweighing and metal detection are the first operations after cartoning (shown). For any given product run, the weights of the first handful of cartons off the line are checked, and the system calibrates for 16- or 17-ct layers to narrow in on the 10.5-oz desired carton weight.

Checkweighing and metal detection are the first operations after cartoning (shown). For any given product run, the weights of the first handful of cartons off the line are checked, and the system calibrates for 16- or 17-ct layers to narrow in on the 10.5-oz desired carton weight.

Cartons are shrink wrapped in poly film from Sealed Air in an Extreme (nVenia) shrink film applicator and shrink tunnel. Dziuda notes that the heat tunnel temperatures don’t have any negative affect on the recently cooled, enrobed chocolate contents of the carton. An inline label applicator from Diagraph is next. On occasion, pressure-sensitive, sticker-style labels are added to the shrink-wrapped cartons for special product runs, but the legacy piece of equipment of unknown provenance is rarely used. Generally, cartons pass through this equipment unengaged.

Cartons then make an abrupt 90-deg turn to the right while maintaining their orientation, so the wider edge of the cartons lead for this brief interval. This is the preferred orientation for case packing operations. Cartons are accumulated and stacked into 4x3, 12-ct configurations as they enter a wraparound corrugated case packer by BW Integrated Systems. The only current format is of 12-ct corrugated cartons, but 30-ct might be on the horizon for the company. Adhesive is applied to the cases by equipment from Nordson within the case packer, the cases are closed, and they travel downstream to the end of the contiguous line for palletization. Cartons undergo a 90-deg turn and are oriented to travel wide-side first into case packaging operations. Once a 3 x 4 stacked format is collected, the block of cartons is pushed into postion in the wrap-around case packer. Adhesive is then applied ahead of palletizing.

Cartons undergo a 90-deg turn and are oriented to travel wide-side first into case packaging operations. Once a 3 x 4 stacked format is collected, the block of cartons is pushed into postion in the wrap-around case packer. Adhesive is then applied ahead of palletizing.

Case coding is done on a Markem Imaje 5940G two-head coder, and palletizing is done via a Fanuc robot arm on equipment from BW Integrated Systems. Cases on the pallet are about a half-inch out of perfect square, so they’d be fairly unstable stacked as columns in a unified orientation. The company uses an interlocking column stack to stabilize the pallets, with a small amount of offset and an open chimney in the center to accommodate the offset.

Pallets are carried a short distance by forklift to a standalone Lantech turntable stretch wrapper to complete the new packaging line. Pallet rates are slow enough so as not to require an on-line pallet wrapper—not to mention other departments make use of the Lantech. Because of the conveyor layout, Sweet’s couldn’t use a traditional lift with outriggers, instead going with a counterweight lift with a heavy and high lifting capacity.

Training and aftermarket support

Kay and Dziuda knew going into this project that training their labor force on the advanced new equipment would be essential for success. Dziuda had worked with Schubert before and was aware of how thoroughly the OEM handles training—that’s one of the reasons he sought it out. But the Schubert training program was new to Kay. Cartons undergo a 90-deg turn and are oriented to travel wide-side first into case packaging operations. Once a 3 x 4 stacked format is collected, the block of cartons is pushed into postion in the wrap-around case packer. Adhesive is then applied ahead of palletizing.

Cartons undergo a 90-deg turn and are oriented to travel wide-side first into case packaging operations. Once a 3 x 4 stacked format is collected, the block of cartons is pushed into postion in the wrap-around case packer. Adhesive is then applied ahead of palletizing.

“Their training disciplines were something I hadn’t experienced from a supplier before,” Kay says. “Beyond the equipment itself, training certainly helped differentiate them. Just the idea that we’re going to get the support we needed was important since we’re out in the middle of nowhere. Their engagement with our maintenance team, with our operators, and with our management was remarkable. To me, that’s a differentiator in future projects; they’re at the top of the leaderboard on who we want to talk to. If you’re going to be in the food business domestically and be competitive, especially confection business, you need throughput. You’ve got to run lean and mean. Downtime kills you.”

At the time of PW’s visit, two of Sweet’s Candy Co.’s maintenance technicians have already visited Schubert’s South Carolina classroom with three more techs lined up to visit.

Results and knock-on effects of the new packaging line

With increased speed and reliability in packaging operations, Sweet Candy was able to increase the speed of the upstream mogul machine by 15%. The entire line now runs at 60 cartons/min at cruising speed, 24 hours per day, five days per week.

“On our older equipment, when we were dealing with product coming at us like it was coming out of a firehose, we couldn’t have imagined increasing speed,” Kay says. “We’ve been so thirsty for the opportunity to fine-tune things and move away from the hand-made, recipe card-driven culture, and instead take advantage of an automated, highly engineered solution. We’ll be able to dial in and hit our spec and stop giving away chocolate. Even if that forces us to increase the size of the candy center, that’s okay. The center is a lot cheaper than the chocolate.” Interlocking pallets are built in an articulated robot arm palletizer, then are forklifted to an adjacent turntable-style pallet stretch wrapper. Stretch wrapping is

Interlocking pallets are built in an articulated robot arm palletizer, then are forklifted to an adjacent turntable-style pallet stretch wrapper. Stretch wrapping is

The cartons themselves are getting a minor upgrade that wouldn’t have been necessary before, when hand-packaging was more common. The lids, which have been essentially using the same design for decades, have a bit of a natural bow to them. Though imperceptible to people, robots could benefit from a flatter pick space. Sweet Candy is working with their supplier Utah Paper Box on a crisper, more consistent lid to dial in on some of the slop tolerances.

“The need to improve the carton really illustrates the theme of where we’re at right now. Everything got a lot more precise with this installation,” Dziuda says. Since the time of PW’s visit, the company has installed a new Aasted Master 1300 Enrober “upstream so that we have better consistency, and we’re a little bit more precise in the chocolate on average, with less tailing, and just making a more consistent product that we’re feeding into the packaging machines. We made a step change on the scrap side for sure, and like Rick said, it allows us to dial in and be a lot more precise than where we’ve been.”

With the recent upstream enrober integration is ironed out, Sweet Candy is looking into diversifying with sizes and counts. Down the road, they would consider doing a single-layer carton, or a shorter cut-off to hit different price points.

“Maybe we can upgrade box shop operations so that we can do different things, holiday sizes, bonus boxes, whatever the case may be,” Kay says. “The one-size-fits-all approach is limiting, but the basics are there with this new installation to move beyond the single carton size.” PW