Supply chain management is having a moment. New programs and processes are getting some major investment, and headlines announcing important initiatives are filling the business press. In 2018 alone, we read: Mars to invest $1B to fix ‘broken’ cocoa supply chain; PepsiCo drives a more digital supply chain; Mondelēz calls for complete sustainability, transparency in palm oil supply chain; and Walmart to lettuce suppliers: Use blockchain.

Disruptive change, including a tsunami of data, is driving these news headlines. Innovations in the creation, collection and analysis of consumer-input and plant-floor data are coming faster than ever before. Savvy supply chain managers are looking at what can help them ride the data wave, rather than be swamped by it. Digital advances beyond the production line, like algorithmic planning, blockchain and mass serialization are all promising new ways to improve customer service, demand planning and more.

Speaking at a gathering of supply chain and enterprise management system professionals, Daryl Plummer, vice president of analyst firm Gartner, recommended using innovation from disruption to transform your company into something new: “Your digital teams need to start having conversations which are rooted in the digital and physical worlds. The physical items need also to be first-class digital assets. The most exciting things happening now are those areas that involve connecting software to the sensors, to the edge and mesh networks out there.

“Sixty-seven percent of organizations have too few large digital investments,” says Plummer. He calls that “lots of disconnected dabbling — random acts of digital.” Now is the time to think holistically about the digital supply chain and about the customer, he and others contend.

Forward-looking data analysis

When considering the digital supply chain, data analytics is a good place to start. What’s new is the move from being reactive to proactive. Traditional data reporting and analysis typically summarizes historical trends. Gartner calls it “descriptive analytics.” Advanced analytics are forward-looking, often combine data from multiple sources, and may use artificial intelligence or machine learning to make predictions. Subtypes of advanced analytics are predictive, prescriptive and cognitive analytics.

According to research sponsored by software supplier Logility, 22 percent of top supply chain executives say they have implemented some type of advanced analytics, while 44 percent say they are planning to upgrade or implement it in the next two years. Supply chain planning and forecasting, logistics management, and customer service improvements are the top three applications for the technology.

IFS and other enterprise software vendors are beefing up their prescriptive analytic functionality and artificial intelligence engines as a result. “We’re analyzing the data to give you the starting point of where you need to go,” says Colin Elkins, global industry director for process manufacturing for IFS. “Rather than reveal a list of all the things that happened yesterday or all the purchase orders you should have expedited, we’re saying these are the five you need to check. We’re trying to turn the data on its end, and give people the start point of their day.”

The use of predictive, prescriptive and cognitive analytics in the supply chain can lead to the next competitive breakthrough, according to Hank Canitz, a former director with Conagra Foods and director of product marketing and business development for Logility. Predictive analytics helps companies get out in front of events and disruptions to determine “what will, or could, happen.” Prescriptive analytics answers the question “what should I do” in order to maximize profits, minimize costs, and/or meet customer requirements, for example.

“Advanced analytics allows companies to leverage the tremendous amounts of data available today, including both structured data, such as from sensors, and unstructured data, such as text and pictures from social media,” says Canitz. “There’s a lot of opportunity for data integration. You can even pull together data from 15 different ERP (enterprise resource planning) systems.” You’re never going to get to one ERP system, he says, but you can get to one planning system.

Such data integration can be very useful as companies lose people due to retirement or to accommodate business diversification and/or acquisitions. Canitz says when he was at Conagra, acquisitions happened all the time and using Logility DAPlink software made data integration much easier to accomplish.

Better demand planning

The algorithms that are generated by advanced analytics can have a positive impact on everything from sales demand planning to distribution requirements planning and more. Logility is focused on algorithmic planning/optimization, which uses software algorithms to synthesize information from multiple data sources to arrive at optimized plans in an automated way. “You can do multiple simulations of a plan without having to export data into a separate BI (business intelligence) system,” says Canitz.

Demand planning might be the single hardest thing to do in supply chain management, so it’s where innovation is being focused. Demand for fresh produce, for example, can vary as much as 50 percent, says Elkins, due to seasonality — ice cream in summer, turkeys for Thanksgiving and Christmas — or the effects of weather on crop yield. Demand planning tools “are still nowhere near where a planner needs them to be,” he says, but ERP software vendors and others continue to improve forecast accuracy.

“You almost have to do a continuous planning process, where you respond as exceptions come in,” says Canitz. “You have a big customer order, a truck runs off the road, you don’t wait until the end of the week to respond.”

As food and beverage manufacturers become more demand-driven, often there is a shift toward more frequent changes in production runs as well. These market requirements must be balanced with the traditional desire for maximum production efficiency. “If manufacturers are not using algorithmic systems to manage inventory, they’re not optimizing their capital,” says Canitz. “Companies are starting to come around to the need for an inventory optimization solution. They can save up to 30 percent by better managing their inventory.”

Gerry Gray, senior director of product strategy for ERP software vendor Plex Systems, says, “The agility with which a manufacturer can plan for and cater to spikes and dips in demand depends on their visibility into inventory levels across the business, and has the potential to greatly impact how they respond to short lead time changes.”

Edge computing sifts plant-floor data

No less important than responding to demand data is analyzing and responding to plant-floor data, which has its own disruptive forces and new technologies. Just a few years ago, the talk was all about moving production data to the cloud. “Now the talk isn’t about cloud computing. Now it’s all about the edge,” says Elkins. “We’re going to see a lot more edge computing devices going in to support supply chain applications.”

John Oskin, CEO of enterprise software vendor Sage Clarity, says, “Advanced manufacturing analytics will help you identify and predict performance bottlenecks in your production, while IIoT (Industrial Internet of Things) edge computing will alert you when downtime happens, and pave the way for quality improvements.”

Edge computing keeps some of the analysis of real-time data out of the cloud and in the devices. According to the Industrial Ethernet Consortium, supply-chain edge computing applications gather real-time data from IIoT in short intervals, and then apply optimization algorithms and manufacturing analytics to adapt plans in ERP systems and elsewhere. “The edge,” in its view, can be the place where computations are made, or it can be where the resulting data is used to address specific business problems. The term “IIoT” can be used to encompass all these plant-floor-data-related innovations.

“IIoT is experiencing rapid adoption, particularly by enterprise-size operations,” says Plex Systems’ Gray. “Through our work with more than 600 manufacturers around the world, we’re also seeing an increase in the number of [IIoT] use cases with high ROI. We anticipate that IIoT adoption in smaller manufacturing operations will also accelerate as the cost of infrastructure technology decreases.”

Blockchain, Walmart and leafy greens

Track and trace software technology is arguably the most important and well-established module of supply chain software because “you have to have it if you want to trade with the retailers,” says Elkins. “Any company today that still has a paper-based track and trace system has one huge risk. Paper-based systems can break a business.”

Enter blockchain technology. Associated in popular culture with bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, blockchain is still very new, but it is enjoying immense interest from manufacturers. What blockchain technology provides is an uninterruptible, unbreakable chain of transactions made between different trading partners — technology that supports track and trace applications.

A blockchain transaction can’t be changed by any partner in the chain, and blockchain doesn’t require a central party to act as a clearinghouse of transactions. There are limitations, such as the fact that blockchain can’t grant permissions-based viewing (everyone can see everything), but a number of companies started experimenting with blockchain specifically and distributed ledger technologies, in general, two or three years ago to generate solutions for specific industries.

The Blockchain Research Institute funds a multimillion-dollar research program featuring more than 80 projects documenting the strategic implications of blockchain on business, government and society.

For the food industry, enterprise software vendor SAP recently convened a Farm to Consumer Traceability Proof of Concept project that included various food value-chain leaders, including Kellogg, Naturipe Farms and Johnsonville, as discussed by Anja Strothkämper, vice president for agribusiness and commodity management for SAP.

The specific goal of the SAP project was “to determine whether a blockchain solution can achieve ‘transparency of genealogy’ — or the ability to view the origin of a given food item from the shelf all the way back to the farm — across the value chain, with the ultimate aim of minimizing recalls and, by extension, reducing food waste,” explains Strothkämper.

“For food brands, an enormous amount depends on consumer trust,” says Strothkämper. “Thankfully, the advent of blockchain technology makes it possible to create a food value chain based on trust and transparency among the various stakeholders. The collective view of the participants was that building a blockchain network not only enables end-to-end food traceability, it also drastically reduces the time required to identify a necessary recall. Consumer health is thus protected, as is trust in participating brands.”

Another way to generate a new global solution quickly is to have a powerful industry player mandate one. Walmart has been experimenting with IBM’s blockchain solution called Food Trust since 2017. In September 2018, Walmart notified suppliers that “all leafy greens suppliers are expected to be able to trace their products back to farm(s) (by production lot) in seconds — not days.” In the same notice, Walmart said, all suppliers of leafy greens to Sam’s Club and Walmart are expected to enable “one-step back traceability” by Jan. 31, 2019, and “end-to-end” traceability by Sept. 30, 2019.

Given that one of the biggest retailers in the world is in the proof-of-concept stage with leafy green vegetables traced via blockchain right now, this technology is clearly on a fast track. Elkins says, “I imagine that every retailer is now running a project very similar to the Walmart project in terms of blockchain technology because they know that Walmart will have a massive edge when they can say, ‘All of our products are validated via blockchain.’”

Blockchain promises to create a single source of truth for any kind of supply chain data and could, for example, be used for farm-to-fork traceability and transparency — “something that still, in a lot of ways, does not exist,” says Elkins.

Gray predicts that “although larger retailer and foodservice companies are the first to provide the consumer with greater visibility into the provenance of their food with blockchain, this will continue to trickle down to smaller organizations as the technology becomes more affordable, efficient and proven for food manufacturers.”

Mass serialization and smart packaging

Some organizations aren’t waiting to jump into a “blockchain adjacent” technology called mass serialization. This product-level identification technology promises to prevent unauthorized product distribution, identify counterfeit products, and engage consumers in personalized ways with products and the companies who market them.

Mass serialization is a form of active and intelligent, or “smart,” packaging that enables every package to be unique. Any data associated with the product in that package — the location of the farm for key ingredients, the specific batch that produced it, details about the batch, etc. — can be noted on the package and be made available to supply chain applications. More importantly, customers can interact with the packages as well, adding data from their end of the supply chain: where they are, when they bought it, and even videos or text sharing their experiences of the product.

In November 2018 in Amsterdam, the AIPIA World Congress convened to showcase the latest advances in smart packaging, including presentations on sensor technology, augmented reality, blockchain and more. Lessons are being learned about why and how brands can bring the power of the digital world to physical packaging and back to the supply chain. Two different vendors presented on their mass serialization efforts with food and beverage companies.

One company, Kezzler, has experience deploying mass serialization on 6 billion products from the food, pharmaceutical, agriculture, industrial and consumer sectors. CEO Christine Akselsen says that “Kezzlercodes” enable manufacturers to build a supply chain of authentic, traceable and connected products that carry their provenance with them. “You can have control of your supply chain by adding batch-level data to an individual product. And you can follow that product’s journey through distribution and sale,” she says. “That enables brand protection because you can know if a product intended for the Mexican market ends up in Brazil, for example.”

Kezzlercodes are “blockchain-compatible,” says Akselsen. “We see ourselves as complementary to blockchain technology, with expertise on the physical side of packaging.” Kezzler has a lot of experience with “old school QR codes” and other digitally printed formats, as well as a partnership with Scanbuy, which produces SKU-level barcodes. Once a Kezzlercode is linked to a printed code on a package, then “theoretically if an end consumer wants to know the origination of the product, they can scan the code to find out the ingredient supplier or identify time and date of production,” she says.

Kezzler presented a project with Mondelēz for a digital-message promotion for Toblerone chocolate bars that involved Kezzlercodes. Kezzler gave every triangular chocolate bar package a custom QR code that could be scanned with a mobile phone so a gift giver could record a personal video message. The gift recipient could then scan the code anytime to retrieve the message. This use of mass serialization technology is designed to encourage customer engagement and could be the basis of a customer loyalty program or feedback system.

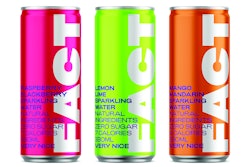

The second company, EVRYTHNG, describes itself as the Internet of Things (IoT) SaaS platform for consumer products. EVRYTHNG released a report on blockchain and other distributed ledger technologies and announced a partnership with a new beverage maker, Almond.io, which will use EVRYTHNG mass serialization technology on cans of FACT, Almond’s new organic, flavored water.

Almond seems almost to be a technology/marketing company first and beverage company second. Rather than retrofit supply chain data into individual products, “Almond is a new ecosystem we’re building on the EVRYTHNG platform that allows brands to digitize their products,” says Almond Managing Director Oliver Bolton. The brand can then do two things: “On the one hand, show ingredients, traceability and transparency and, on the other hand, create their own mini-cryptocurrency to reward consumers,” he says.

FACT is the first brand in the Almond ecosystem. In 2019, Almond plans to add a second brand, What a Melon, and hopes to attract other B Corps wanting to offer transparency to consumers. (B Corporation certification, issued to for-profit companies who want to “balance purpose with profit,” has been granted to more than 2,600 companies, many of which are in the food and beverage industry.)

What to do now

Given all the technologies that exist today, Elkins from IFS has a prediction: “One day, sooner than we may think, when you buy a package of greens, say, from your retailer and put it in your fridge, your fridge will know the batch number or lot number. Then, when a recall is put out by one of the manufacturers — saying they’ve detected E. coli in these batches processed in these facilities distributed via these routes — your fridge will alert you that you have a problem with one of the products inside so you can protect your family.”

Smart fridges exist. Mass serialization technology exists. The relevant software to manage wireless alerts exists. In fact, according to Gartner, by 2020, IoT sensors will be in 95 percent of electronics for new product designs. That means sensors in cars, kitchens, vending machines and retail outlets. “All we need is someone to join up the systems,” says Elkins. And as soon as someone does, others will as well.

So, “think where the world will be in three to five years and work backwards,” says Elkins. Plan now to turn disruption into innovation and supply chain success.

Read more in "Chicken farmers improve traceability" for how the Chicken Farmers of Ontario implemented SAP technology to increase real-time visibility and response time.

Read more in "Almond.io embraces mass serialization" for how Almond.io is using mass serialization to improve traceability and create deeper connections with consumers.