Facility operations that run like clockwork are not the product of good luck or chance but are the result of careful planning, attention to detail, and the implementation of robust procedures. These programs identify potential problems and implement solutions ahead of time to ensure maximum production output, regulatory compliance, and preventive measures that will mitigate anticipated food safety issues. This article lists 10 common food safety problems and how to solve them.

1. Management and worker culture

In the past two years, establishing a food safety culture has been the topic of articles in trade journals and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) documents. The problem is twofold. First, there is no exact definition of food safety culture, and second, it is not always apparent whether a plant has achieved a desired level of food safety culture.

Management must define its food safety goals and outcomes, and ensure employees are aware of the objectives and participate in achieving the goals. Management’s role is to establish and maintain consumer trust, produce safe food, meet regulatory compliance requirements, and develop and implement a safe-food attitude. Its role begins with establishing a food safety culture and providing resources, food safety awareness at all levels, and training and commitment. Measurements to ensure objectives are met are essential.

2. Plant design

Newer facilities generally have an advantage over legacy operations, since typically, older plants started as small plants that grew asymmetrically as production demands increased. Plant expansions to accommodate more throughput can alter product flow, airflow, worker contact, warehousing material movement, sanitation practices, and a host of other issues related to maintaining food safety. It is critical to involve the food safety team when expansions are planned. These team members can identify where sanitation and hazard mitigation steps may be compromised and where new potential hazards may be introduced due to facility changes.

With biosecurity becoming a part of regulatory and liability concerns, management must include food defense mechanisms as part of a facility’s safety and security measures. The food safety team should examine and modify food safety and food defense plans, as needed, for plant design changes, especially in high-risk or hygienically sensitive locations.

3. Processing equipment

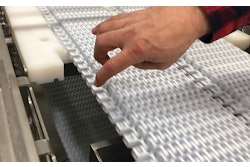

Purchasing new equipment or modification of existing equipment should involve the food safety team. Poorly cleaned and sanitized equipment (e.g., conveyors) can harbor microbial contamination and, in some cases, can collect allergenic product, which can contaminate a nonallergenic product produced on the same line.

The food safety team should consider where the equipment is located (inside, around, and under the machine); the internal and external parts to be cleaned; the cleaning solutions and methods (e.g., dry clean, wet clean, clean-in-place); and the direct and indirect parts of the equipment that contact food. Procedures should follow and validate the machinery maker’s cleaning and preventive maintenance guidelines and incorporate them in the plant’s standard operating procedures (SOPs).

4. Materials control

Materials that enter the facility must be addressed from a food safety standpoint. Loading dock staff should have the authority to “bump the load” if the ingredients, packaging materials, or other supplies or goods do not pass a clean and filth-free visual inspection. A first-class operation will manage chemicals and ingredients with care and implement proper handling and storage to avoid cross-contaminate chemicals, allergenic ingredients, and the mixing of raw and finished products.

5. Sanitation programs

The production of safe foods for humans and animals requires a rigorous foundation of cleaning and sanitizing practices that include well-written and well-executed prerequisite programs (PRPs) that cover, at a minimum, the regulatory requirements found in current good manufacturing practices (cGMPs). It is not uncommon to discover a recall was due to a poorly developed PRP, inadequate training, or a failure to properly execute a PRP.

A comprehensive cleaning and sanitation program should address allergens, filth, and waste materials, as well as potential pathogens. A well-designed sanitation program should organize, implement, and monitor an effective sanitation program. The first phase is to develop a program that produces and maintains a clean and wholesome environment for food production, processing, preparation, and storage.

Next, the program must be implemented as designed and operated without exception. Finally, the program must be adaptable to change, so that continual improvements can be made.

6. Hazard identification

The hazard identification and analysis steps for products regulated by Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) or the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) make up a complex process that requires extensive food safety knowledge and processing skills to administer. Potential hazards (e.g., biological, chemical, physical, radiological, or intentional adulteration) must be addressed and identified. The regulatory requirement and solution should have a preventive controls qualified individual (PCQI) oversee the hazard analysis and manage the development of the food safety plan. The PCQI can be an employee or consultant who has completed training in the development and application of risk-based preventive controls or is otherwise qualified through job experience.

7. Food safety, FSMA, or HACCP plan

Food safety plans should be product specific, although like products can be grouped. Don’t use a generic food safety plan as a substitute for an in-house plan with your specific products and equipment. The plan is a dynamic document that needs daily attention to ensure it is being followed; ensure proper records and documentation are maintained; and document problems or changes in operations, especially when corrective actions are taken to find the root causes of problems.

8. Training

Having poorly trained workers will likely result in problems that could have been prevented. Training programs are applicable for management but are also essential for line workers and those with food safety responsibility. Training starts with communication by management to line workers about the food safety culture. Training is needed for staff members who design and oversee the sanitation (cGMP) and food safety plan. Line workers require job-specific training, along with testing to ensure they comprehend procedures, compliance, and effectiveness. Training should be documented, and refresher courses planned as needed.

9. Verification audits

Working in a closed production facility environment can sometimes cause complacency. Periodic audits, by internal and/or external personnel, can help identify potential issues and provide suggestions to prevent future problems. Audits can help verify the sanitation and food safety plans are effective, and document that regulatory and food safety measures are designed and implemented correctly.

10. Customer issues

Employees must be aware of issues that could affect production by keeping a close watch on the actions and issues of regulators, competitors, and international food producers. Food safety team members also need constant contact with customer service staff to see if claims or consumer complaints uncover a problem.